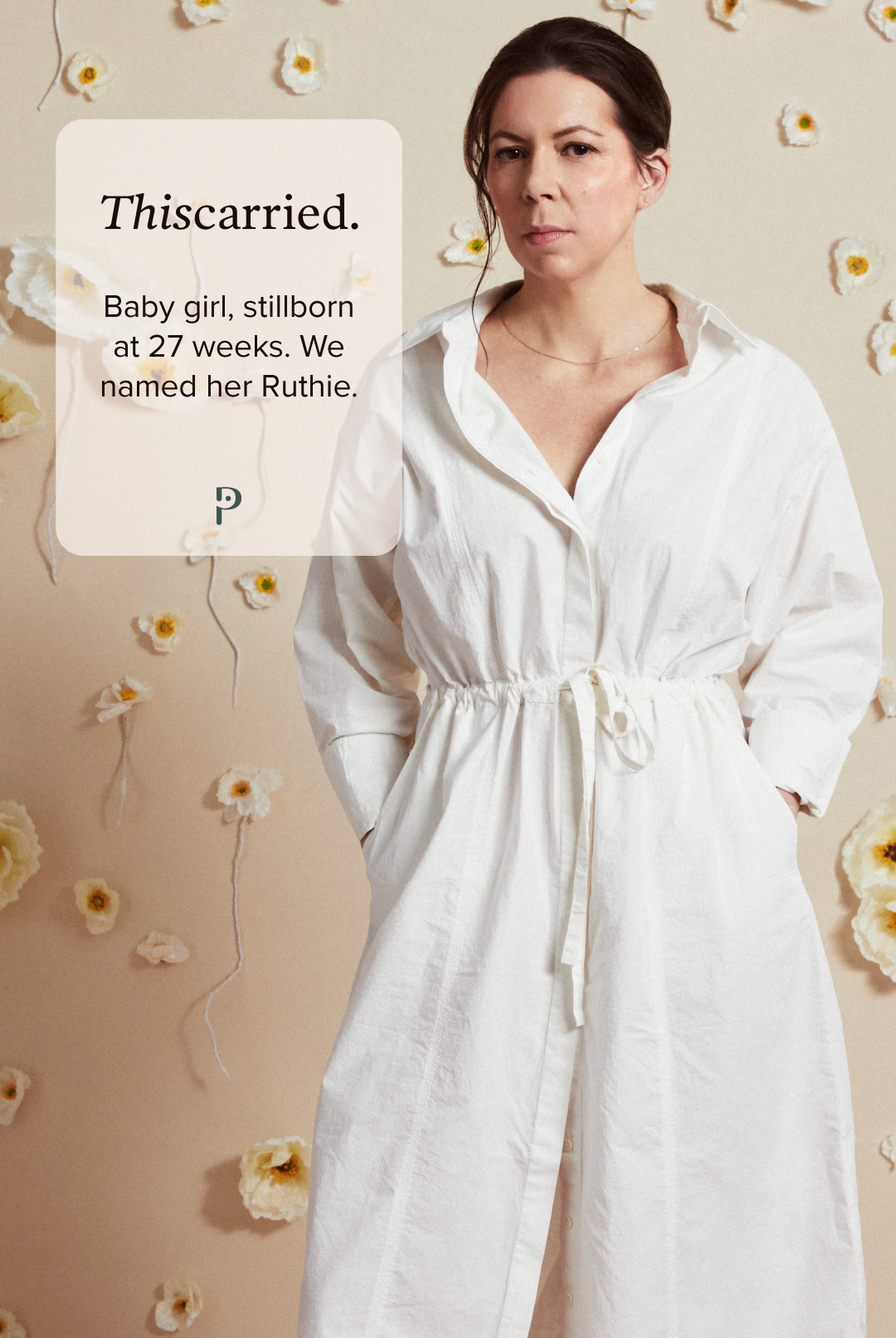

Kristin & Chad’s journey through stillbirth

“After labor, the hospital policy is that you have to be escorted out in a wheelchair. I remember telling the nurse I was going to walk out. I needed to walk myself, standing as tall as I could, one foot in front of the other. I will never forget that hallway. I’m sure about that.”

—Kristin, on leaving the hospital after her daughter was stillborn at 27 weeks

Sitting down with Kristin & Chad

We’re so grateful for your vulnerability in sharing your story with us. Can you describe your experience with loss?

In 2019 I had a miscarriage. It was a really intense, awful 24 hours. But it was also something I found a way to make sense of: This wasn’t meant to be. I was ok. My husband, Chad, and I got pregnant again several months later. It was a girl and we were excited. Then on November 3, 2020 our daughter, Ruth May Ohnstad Murphy (she goes by Ruthie), was stillborn. It was a total shock. No warning, no issues we knew of. I went to a routine third trimester appointment and there was no heartbeat.

That evening I was in labor. I went through all the labor things. It knocked us on our asses. Losing a child—of any age—will forever change your life and who you are as a person. I’ll never forget the social worker who was assigned to us in the hospital. She pulled me aside and said, “Marriages often don’t survive this. Do you want a therapist?” Yes. OMG yes. In that moment I was, and still am today, so grateful for that social worker’s honesty and directness. Chad and I were privileged enough to have access to and to be able to afford one of the best therapists in NYC who specializes in stillbirth (which, until then, I didn’t even know was a specialty or should be). I’ll call her Dr. M. Two days later, we had our first conversation with her. I will also never forget the first question Dr. M. asked us. Simply: “Tell me about your daughter, Ruthie.”

Right then, we felt seen in ways no one else could see us. Dr. M. gently helped us start to pick up the millions of pieces we had both been shattered into and try to form them back into a new whole: as individuals, as a couple and, most importantly, as parents—an identity we didn’t know if or how to claim.

Chad: It just felt like such a routine kind of appointment and then to hear that news was devastating. So yeah, I was illegally parked, double parked, just in Manhattan. Just sprinting across the street and going up the stairs as fast as I could.

Kristin: I remember you came into the room and she said, "I'll give you a moment together." And the image was still on the screen and I remember that. And I remember we stood up and we just hugged each other and I just remember saying to you in your ear, "I don't want to do this, I don't want to do this." Because at that point, the doctor explained what needed to happen next, that I had to go to the hospital, get induced, go through labor. And I remember asking her, "Is there any other option? Is there any way to not have to go through labor?"

Unfortunately, I learned firsthand the difference between a miscarriage and a stillbirth, given I've had both. With a miscarriage, in my case, there was no heartbeat. And the advice was, "Go home. Give it some time, go home, come back, call, when it's over." Whatever that means and that was that. I think for a stillbirth, I was naive, I mean, I think we all are. No one knows what that is until you go through it, really, so I didn't actually know the questions to ask. But I think I knew intellectually I had to go into labor, but I think I was naive in asking a lot of questions about why and if there was another option. And in the moment it felt like a pretty mean thing to have to do. And I continue to learn through the process, how there really is no difference in a stillbirth, in my case. Everyone is different, but in my case, between going into labor with a live baby and a baby who's not going to make it. The only difference is they give you way more drugs and so it's more intense.

Can you tell us about finding out there was no heartbeat and what happened next?

What was it like going through IVF after loss?

After Ruthie died, we had her genome sequenced to try to get answers about what happened. We learned that I had passed an incredibly rare gene mutation, called EPHB4, onto her that I didn't know I had and there was virtually no research on. This gene mutation can kill babies young, either before they are born or shortly thereafter. This mutation also had implications for me, so that set off a long journey of doctors appointments to make sure my health was stable. Chad and I decided to do IVF so we could weed out the gene mutation—the only viable option for us to try to have a baby.

After 2 years, 4 egg retrievals, 1 custom genetic test (the science available today is truly amazing!), and 2 failed embryo transfers, we got pregnant with the last embryo we had. On February 10 of this year, our boy was born. We named him Hayes Eliot Ohnstad Murphy. Ruthie has a little brother. And we know he knows he has a big sister. Hayes has a smile that is big and bright enough for both of them. Getting Hayes here required navigating so much loss: miscarriage, stillbirth, the limits of reproductive science, IVF rounds that produced no viable embryos, failed embryo transfers, and chemical pregnancies. We’ve done it all. But our marriage is strong. We are strong. We are parents two times over (I can say that now with confidence!).

“We get up everyday. We do the work. We keep things in perspective. We choose love, instead of fear. Then we get up the next day and choose it again.”

KRISTIN, ON STRENGTH AFTER LOSS

Did you each navigate the experience similarly or differently? How did it affect your relationship?

Kristin: We navigated it together. We were determined to do therapy together because we knew it was essential that we understand each other’s needs and what we were each going through. Our paths were not the same. But we made sure to pay attention to both our own path and each other’s. Chad, as a guy, had less emotional support in some ways. People asked about me, and less about him. He had a few friends — other dads — that were a real lifeline for him. I had more emotional support, but also had a physical recovery to navigate, like when I started producing milk after we got home from the hospital — a lonely and mean reminder.

We never lost sight of one another in that way. We checked in with each other constantly (sometimes just a simple “Where you at right now?”). In the early days, we checked in hourly (often with just a look) and, as time passed, that moved from daily to weekly and so on… I think we were terrified that if we didn’t navigate especially the early days of grief and dark together, we might lose each other too — and that was not an option. I remember very clearly the first time after Ruthie died that we laughed together, like uncontrollable belly laughs. That felt like hope that we could make it through this.

Chad: It was a blur, at the beginning at least, and we were feeling around in the dark a little bit at first but when we were in the hospital, there was a social worker who pulled us aside and asked if we wanted to have a reference to speak to somebody and we said absolutely without thinking about it much. I hadn't done therapy before, but Kristin and her strenght, was like, “I want the best person that you know of” and so I followed her lead and that was it. So we were introduced to our therapist and we wanted to do it together because it just felt right. It was the thing that we both went through. Kristin wanted to acknowledge that I was going through something awful as well. It was different, but needed recognition and I needed an outlet. I didn't want to be that stereotypical male who would be too afraid to do something uncomfortable.

We’re dedicated to destigmatizing the unspoken parts of loss and shifting the narrative. Did you experience feelings of shame around your loss? Were there aspects you felt like you couldn’t talk about or felt judged for?

We didn’t feel shame. We felt a lot of other things. I felt unsure. I remember asking people if they wanted to see photos of Ruthie and of Chad and I and her grandparents holding her, but I never pushed. Not everyone wants to see those images. I remember telling people an edited or “cleaner” version of what happened, depending on how much I thought they could handle — I still do. Giving birth to a dead baby is a very raw and hard and vulnerable thing that not everyone wants to hear. And, to be clear, I don’t always want to share. I still choose when and to whom and how much to share (that’s an important part of healing). But it’s easy to only talk in general, PG terms — to paper over the details — such that stillbirths become less real and honest. At the right times, we need to talk about the real stuff.

Sharing photos of Ruthie is important when people want to see them because it makes her real. All parents are excited to share pictures of their kids. It's not different than that. The handful of images we have honor Ruthie’s little body and life. They honor us as her parents, and her grandparents — my parents — who flew across the country and got to the hospital in time to hold her, and also suffered from deep loss from losing their granddaughter. We are unsure how to talk about grandparents who had a grandchild who was stillborn. That experience lives in the shadows too.

Sharing details about what stillbirth is really like is important because it honors the experience that I, Chad, and our families had. I remember people, with good intentions, saying things like, “When you do have a baby, go for the epidural.” I did have a baby. I did go through labor. I did have an epidural. I just didn’t leave the hospital with a living baby. I left her there. After all the pregnancy and labor my body and mind and heart went through, we had to leave her there.

After labor, the hospital policy is that you have to be escorted out in a wheelchair. I remember telling the nurse I was going to walk out. I needed to walk myself, standing as tall as I could, one foot in front of the other. I will never forget that hallway. I’m sure about that. For me it was about power and confidence and, in retrospect, I couldn't have said this at the time, but I think it was about a first step to integrating that loss into me as a person, and into my life and our life, and taking that first step, physically taking the step, but I didn't want to leave the hospital feeling broken in a wheelchair. It was, even in that moment, it was a choice to not feel broken.

How do you stay hopeful navigating life after loss?

Everyday Chad and I do the work to make all this loss and joy part of who we are—to embrace it and integrate it. The mantra we say to ourselves and each other is: We choose love. We get up everyday. We do the work. We keep things in perspective. We choose love, instead of fear. Then we get up the next day and choose it again. And Dr. M. was right: It never goes away, but we get better at carrying it all, so it does get easier.

Ruthie has a tree and bench dedicated to her in Prospect Park in Brooklyn. We go there often. Every November 3 we take the day to just be together and honor her in some way. Her urn and her footprints are in our room.

You’re not in this alone

Poppy’s Loss Hotline is available 24/7 in our app, for immediate loss support.

Poppy’s Loss Care Guides

Want to share your own Thiscarried story?

Through honest storytelling and shared experience, we can help each other feel less alone, tap into our own strength, and eradicate shame around pregnancy and infant loss.

Download and share the Thiscarried tile with your own story of loss, to help us destigmatize these experiences.

#Thiscarried | @poppyseedhealth